The above advertisement was running in Liverpool newspapers in May 1869 and publicised the printers’ latest pamphlet:

‘THE GREAT MASONIC TRIAL of TORCKLER v. TATTERSALL for ALLEGED FALSE IMPRISONMENT AND OBTAINING MONEY UNDER FALSE PRETENCES‘

In the foreword, the anonymous author tells the readers:

“This case, which has now occupied for some time a very prominent place before the public, has evolved so many peculiar circumstances calculated to warn the benevolent portion of the community and especially all Ministers of Religion, that it is considered desirable to print in the form of a pamphlet for general circulation, this account of the Trial as copied from the notes of the shorthand writer. The facts of the case speak so strongly for themselves that not one word is being added by way of comment.

“For the large body of Freemasons whose powerful and unsectarian influences for good are well known…this pamphlet may be useful in the future arrangements of their Special Committees appointed for the purpose of proving and assisting worthy and distressed brethren.

“Under any circumstances, it is considered most desirable that the strange career revealed during the course of this lawsuit, by self-confession, should operate widely as a safeguard for the public and social morality.”

The author then goes to issue a forerunner of the advice still issued today about unsolicited approaches: “be most cautious in giving credentials to possibly unworthy and, in many cases wicked persons, and thus avert the great distress and anxiety of mind, in which at all events, one family has been most unjustifiably involved.”

So who was ‘Torckler’ and what was it all about?

To unravel the ‘extraordinary revelations’, we need to go back many years before the 1869 ‘GREAT MASONIC TRIAL’ and unfold the curious tale of William Young Torckler, military veteran and self-titled ‘Teacher of Sanskrit, Persian, Hindustani, French, Latin, Greek, Fortification, Algebra, Mathematics, and English Literature in General’……….

| PART ONE ‘….. be exemplary in the discharge of your civil duties by never proposing or at all countenancing any act which may have a tendency to subvert the peace and good order of society….’ (The Ancient Charge) |

It was a hot, wet, steamy and oppressive night in Sultanpur, in the dominions of the King of Oudh, on the 9th of August, 1829. The climate in this part of India (now the state of Uttar Pradesh) was rarely ideal for an Englishman and the middle of the rainy season could be particularly unpleasant. The large garrison station was perched high on the side of the steep valley above the river Gomti and the force of the torrential rain bouncing down on one’s head was particularly disagreeable, so Lieutenant Phillip Goldney, of the East India Company’s 4th Regiment Bengal Native Infantry was very grateful to be able to relax in the relative comfort of his bungalow.

He was comfortably settled with a glass of wine, attended by his servants, looking forward to spending a restful Sunday evening with his books before starting his spell on duty the following day. But the peace was suddenly and rudely shattered when a young man burst into the bungalow armed with two loaded double-barrelled pistols, angrily demanding that Goldney should immediately sign a piece of paper he was waving in the air.

Shocked and enraged, Goldney yelled at him to get out of his house and shouted for his servants to throw him out. A violent struggle followed in which Goldney drew a revolver and pulled the trigger, but it failed to fire. The intruder then fired shots at Goldney– all of which missed – and then hurriedly made his escape and took cover where he was quickly found and taken into custody. The intruder was Lieutenant William Young Torckler and this sorry few minutes of mayhem was to define much of the rest of Torckler’s life.

Born in 1804 in Calcutta, William was the son of Peter Adolphe Torckler and his second wife, Eleanor. In the late 18th century, Peter, who is believed to have been an émigré from Riga in Latvia, was a clockmaker working in Red Lion Street, Clerkenwell, London, and was admitted into the Jerusalem Lodge (now No 197) at the Jerusalem Tavern in Clerkenwell on January 1st, 1780. No initiation date is shown in the Lodge register, so Peter may have been a joining member from another unknown Lodge.

Ironically, given the desperate shortage of money that Peter’s son, William, seemed to suffer throughout his adult life, a magnificent automaton clock featuring a bejewelled model of an elephant, which was made in London by Peter in around 1780 and was once owned by the Shah of Persia, was sold at Sotheby’s in 2012 for £1.4m! Another of Peter Torckler’s superb automaton clocks, incorporating twisted glass rods to simulate a waterfall, is currently housed in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

Peter wed his first wife, Mary Cramillion, in Holborn, London, in 1772 and, in around 1795, they moved to Calcutta with their son, Edward where Peter became a partner in the mercantile firm of Howell and Torckler dealing in imports and exports with the Far East. Mary died early in 1799 and, at the age of 52, Peter married his second wife, 30 year-old Eleanor Isacke, in Calcutta in January of the following year. This marriage produced seven more children, three girls and four boys, of which William Young Torckler was the third child.

William was educated in England and at the age of 17 in 1821, he was commissioned into the East India Company’s forces. The Company, originally formed by Royal Charter on December 31st, 1600 under the name the Governor and Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies, was initially the venture of London businessmen importing spices from South Asia. Over the next century, trade was expanded to include cotton, silk, indigo and saltpetre and was also extended to other parts of Asia. However, the Company found its existence threatened by the actions of foreign Governments seeking a slice of the action and, to counter the threat, set up its own military forces – thereby becoming almost an imperial power in its own right. The British Government began to influence the affairs of the Company towards the end of the eighteenth century, but did not take full control until native troops in the Company’s army mutinied in 1857 – many years after the end of William’s military service.

After surviving a shipwreck on the voyage out to India in February 1821, William served in several different regiments of the Company’s army and, by 1828, he had progressed from Ensign to the rank of Lieutenant in the Company’s 4th Regiment of the Bengal Native Infantry stationed in Sultanpur. However, although events related later in this story demonstrate that he could ‘turn on the charm’ when it suited him, he was not popular with his brother officers and seems to have been rather pompous, arrogant and hot-tempered. Coupled with a tendency to occasionally become violent, these characteristics didn’t endear him to his colleagues.

Greater ill-feeling started brewing when he was appointed as Quarter Master and Interpreter for the regiment ahead of other officers who believed themselves to be better qualified than William. As the months passed, arguments broke out – matters went from bad to worse and finally boiled over when accusations of improper conduct were made against William.

Angry insults were traded and William issued a challenge to a duel to his principal accuser, Lieutenant Phillip Goldney. The commanding officer tried to cool the situation by arranging for William to be posted elsewhere, but, believing he would be joining his new regiment in unfavourable circumstances unless his character was cleared of the slurs cast upon it, William did not let matters rest there. He drew up a written statement retracting the allegations and took it to Goldney’s quarters to demand that it be signed – leading to the events set out at the start of Part One of this tale.

Full details of the accusations against William are lost in the fog of history, but it is known that Goldney had heard and spread rumours that William was ‘in the habit of wearing a native dress and was connected with some fellows in the neighbourhood’. Hardly a damning indictment today, but, in the East India Company’s forces back in 1829, fraternisation with the natives, except by very senior officers for diplomatic purposes, was soundly discouraged and could result in disciplinary action.

After a few weeks in a military jail, on November 19th 1829, William found himself on trial before a court-martial held in Cawnpore on a charge of ‘unlawfully, maliciously and feloniously firing a loaded pistol, or two loaded pistols, at Lieut. Phillip Goldney with intent to murder’. At the trial, Lieutenant William Palmer officiated as Deputy Judge Advocate-General and Captain Robert Adair McNaghton appeared for the defence. According to Torckler, there was bitter hatred and rivalry between Palmer and McNaghton which was abundantly displayed throughout the proceedings.

Torckler was, of course, no shrinking violet and was subsequently admonished for the ‘harsh and scurrilous strain in which the prisoner indulged in his defence……..the employment of such terms of scurrility, as being disgraceful to the profession of arms, and which only recoil on the heads of those who, losing sight of their own dignity and that of the profession, make use of them’. The proceedings seem to have been a tremendously bad-tempered affair all round!

According to Torckler, the prosecutor, Palmer, had been officially censured shortly before the trial and had been warned that his continuance in office depended on him showing greater competency. Apparently, in several previous cases, Palmer had been defeated by McNaghton’s skill as a defender – which is why there was no love lost between them. As a result, Palmer was determined that Torckler would be found guilty and, to ensure this, he allegedly conducted a secret vote where each member of the court-martial wrote his verdict on a slip of paper. The slips were then handed to Palmer, who pronounced a guilty verdict without showing or announcing the content of each slip to anyone else. Torckler was then sentenced ‘to be hanged by the neck until he be dead at such time and place as his Excellency the Commander-in-Chief may be pleased to direct’. This was the first time a court-martial had pronounced a death sentence in India since 1815.

Fortunately for Torckler, the Commander-in-Chief, Lord Dalhousie, although approving the guilty verdict and soundly berating Torckler for his behaviour with his brother officers and for his ‘scurrilous conduct’ and the acrimonious proceedings at the court-martial, decided to remit the sentence. He recommended, instead, that Torckler should be suspended and dismissed from the service. The suspension took immediate effect, but the dismissal took some time, and he was eventually officially dismissed in 1831 and was granted an annual pension of £70.

Torckler claimed that he then joined the Royal British Grenadiers – later the Royal Oporto Grenadiers – and served on the side of Donna Maria in the campaign to liberate Portugal during the usurpation of Don Miguel. In his book ‘Sketches in Portugal during the Civil War of 1834’, Sir James Edward Alexander describes the regiment as ‘being much in want of new clothing, having old blue jackets with red facings’ and goes on to say there were ‘some most determined villains in the shape of officers who joined the Liberating army from England – swindlers, liars, drunkards and duellists’! Although it was promised that the British soldiers would ‘get land, or £40 in money, at the end of the war’, the promise was not kept.

However, William can only have served in Portugal for a matter of a few weeks as he was back in England by 1832 – two years before the war ended – where he wed his first wife, Frances, in Shoreditch in London in May of that year. He claimed to have held the rank of Captain in the Grenadiers, but doubt was publicly cast on this claim in the 1869 “Great Masonic Trial” when he was said to have been ‘little more than a cadet’. On the ‘calling cards’ he was using at the time of this court action, he announced himself as ‘Captain Torckler, late of Her Majesty’s Indian Army’. This is despite the facts that the ‘Indian Army’ in which he’d served did not become ‘Her Majesty’s’ until 25 years after he’d been dismissed from it, and neither did he ever hold the rank of Captain in that army!

After his reprieve from the sentence of death, you may well think that William would thankfully have counted his blessings along with his his pension. £70 per year was a sum not to be sneezed at – it was more than double the annual earnings of agricultural labourers who comprised almost a quarter of the population at that time and was also higher than the average wage of skilled workers in many trades including building, shipbuilding and mining. He could have settled down and got on with his life with his new wife, considering himself lucky to be alive with a guaranteed income for life – but it was not to be.

Virtually his first act as a civilian was to try and pressure Lord Dalhousie to institute a public enquiry into the conduct of the court-martial by Palmer and grant a pardon. This was refused as the C-in-C had already remitted the sentence and saw no point in conducting an enquiry. Palmer had also been removed from his staff position – albeit for alleged embezzlement from the mess funds, of which he was treasurer, rather than for his conduct as a prosecutor. But Dalhousie did tell Torckler that he would refer his case to the King for his consideration on the question of a pardon.

Since the date of his suspension, William had written letters in which he bemoaned his treatment and wrote a long ‘memorial’ of around 50 pages to the Directors of the East India Company in which he unsuccessfully petitioned for restoration to his regiment and his rank along with back-pay and compensation. Although he had clearly committed the violent act with which he was charged and had only been lightly punished, he seemed to believe that Goldney, his accuser, along with Palmer, the deputy judge advocate, were wholly responsible for his unwarranted dismissal.

Goldney subsequently rose through the ranks to Lieutenant-Colonel and, in 1857, was the commissioner of the Eastern Division of Fyzabad when he was murdered by mutineering native troops. Torckler’s comment on the murder was that it was ‘divine vengeance’ – his bitter feelings towards Goldney obviously hadn’t diminished much over the 28 years since their altercation.

In the printed pamphlets and letters Torckler produced in his long campaign against his conviction, many of which ask for financial donations to help him restore his reputation and obtain compensation, William bitterly complains about his treatment, blames everyone else involved for his plight, and moans that no-one has made any serious attempt to help him. Had justice not been denied to him, he immodestly claims, he ‘would have attained the rank of Major-general or, at least, of full Colonel’.

As evidence of the unfair treatment he alleges he received, he cites cases of other members of the Company’s forces who had been court-martialled and (in his opinion) had not been as heavily punished as he was. Amongst these was the case of a Major Bartleman, of the 44th Native Infantry, who had been found ‘guilty of conduct unbecoming the character of an officer and a gentleman, in having at Barrackpore, in pursuance of an endeavour to seduce the affections of Mrs. Shelton, wife of Lieutenant Shelton, 38th Light Infantry, written to her on or about the 22nd of August, 1850, a highly unbecoming note’.

Mrs Ellen Clarissa Shelton was Torckler’s niece, the daughter of his sister, Eleanor Elizabeth and her husband Richard Laughton. This may have coloured his view of the incident, but his opinion that Bartleman’s offence of attempted seduction by writing a note was as serious as Torckler’s own offence of attempted murder by firing pistols at Goldney, does illustrate Torckler’s somewhat warped sense of judgement in relation to his own conduct!

In his pamphlets, William was also not averse to ‘name dropping’ – for example, he lets his audience know that the sister-in-law of his defender at the court martial, Captain McNaghten, was ‘Miss Emma Roberts, the distinguished authoress’. He also provides a series of testimonials, mainly from people who had died long before publication, which gushingly praise his character and skills. Readers of this book may judge for themselves as a pamphlet in which many testimonials appear is freely available on-line, but it appears that several of the them display the same verbose writing style as Torckler himself and mention his conduct ‘towards his widowed mother and orphan sister’ in glowing terms.

In the 1869 “Great Masonic Trial”, it was revealed that a testimonial from a Major-General Burrell, which Torckler was using in his fund-raising efforts, was acquired, along with cash, by what amounts to blackmail – the Major-General was having an extra-marital affair and Torckler was being paid to conceal this from Burrell’s wife!

Amongst his litany of issues, Torckler writes of himself, in the third person, in block capitals, ‘HE HAS PECULIAR CLAIMS UPON THE SYMPATHIES OF HIS MASONIC BRETHREN’ and hopes they will ‘BE FAITHFUL TO THEIR ANCIENT ORDER AND DO THEIR DUTY WITH FRATERNAL LIBERALITY’. He then adds a footnote, again writing about himself in the third person –‘his appeals to the Masonic fraternity and his former brother officers have alike been productive of little or no advantage to him; the latter, for the most part, pleading poverty, and the former, that it is not a Masonic question’.

There is no record of the lodge membership of a ‘William Young Torckler’ in the available registers of the United Grand Lodge of England but it seems he may have been a member of a Scottish lodge. The following letter appeared in the Freemasons Magazine and Masonic Mirror of October 1868 – probably from a Mason who had been approached by William for cash: “Can any of your readers or correspondents inform me, through your columns or otherwise, if they know the present address of a ‘Captain Torckler’. Can they also inform me if he is a Freemason, and if so, in what lodge was he initiated, and when, and of what lodge he is now a member?—P. Z.

The following reply appeared in November: “Dear Sir and Brother, – In reply to the inquiry of your correspondent, P. Z., “Captain Torckler is at present residing at Tranmere, Birkenhead. The No. of his lodge is No. 25 (S. C.) He is not a member of any lodge here. He has obtained relief from the lodges both in Liverpool and Birkenhead. Yours fraternally, P. G. S. (Note: Lodge No 25 in the Scottish Constitution is Lodge St Andrew of St Andrews)

William himself testified under oath in the 1869 “Great Masonic Trial” that he had become a Freemason in 1853 and admitted that he had sought financial assistance from various lodges and individual members on various occasions since then.

Freemasonry also ran in the family – his father, Peter Torckler, joined The Jerusalem Lodge in London in 1780 and his brother, Peter Arnold Torckler, was initiated in 1824 in the Lodge of Courage and Humanity No 823, in Dum Dum, Bengal. William’s sons Frederick and Theodore were also Freemasons for a time – Frederick in Tuscan No 1027 in Shanghai, China, and Theodore in Onslow Lodge No 2234 in Guildford.

After the failure of his attempts to obtain redress from the East India Company, William started a legal action in the Court of the Kings Bench in London during 1834. In the action, he sought £5,000 compensation (today’s value is about £450,000) from Colonel Michael Childers, the President of the court-martial, alleging that he ‘unlawfully and negligently and in violation of his duty did suffer and permit a verdict of guilty ….without first taking the votes of the members of the court-martial’. However, shortly before the case was due to be heard, William withdrew the action, saying later that that he could not afford the legal costs

This was the first time, but not the last, that William would start a legal action for damages only to abandon it at the last minute – and, as will be seen later in this tale, he allegedly failed to pay any legal costs incurred by either himself, or by those he unsuccessfully sued.

| PART TWO ‘…… let me recommend the practice of every domestic as well as public virtue…..’ (The Ancient Charge) |

After William married in 1832, his first son, Robert, who was born five months after the wedding, was quickly followed by Frederick and Harriotte – they were both baptised at the same time in 1834 and may have been twins. By this time, the family had moved from London to Carmarthen in Wales and William had started offering his services as a tutor. He alternated between using the ranks of Captain and Lieutenant when referring to himself and one of his business cards at the time billed him as follows:

In the first few years of the marriage, life seemed to settle down for a while. The family moved from Wales to Bristol and set up a small school in The Mall at Clifton which they advertised as an ‘Establishment for Young Gentlemen’, with William tutoring in his specialities. Four more children were born, one of whom died in infancy in 1839, and, in between nursing the children, Frances, helped out in their establishment by giving lessons in French.

But William’s hot temper soon re-emerged and the couple separated in the summer of 1841. William was living in Bath with two of the children and Frances was living in Bristol when, in November 1841, William was brought to the Police court in Bath on a charge of assaulting Frances. The press report says ‘the agitation she exhibited when called upon to give her deposition interrupted the proceedings for a full quarter of an hour’. She had been visiting the two children who lived with William, when he attempted to detain her, locked her in a room, beat and gagged her and ‘used her very ill’. On a previous occasion, she told the court, he had threatened to stab her ‘in a fit of jealousy and passion’. Frances had no witnesses, but William produced one who offered the opinion that William had only acted as ‘a husband is justified in doing towards his wife under such circumstances’!

William was called upon to enter into recognizances to keep the peace in the sum of £10 from himself and, oddly, £20 each from two strangers to him ‘who generously came forward and volunteered to bail him’ – a result of an example of the charming nature that William could sometimes display when it was to his advantage? The sureties being accepted, William was discharged.

A year later, a warrant was issued charging William with abandoning Frances and his children and leaving them ‘chargeable to the parish of Clifton’ which had expended £100 on keeping the children in the parish workhouse. One child died whilst in the workhouse and the others were there for almost a year before they were taken out by Frances who was then being financially supported by her brother ‘who had married a rich lady’.

William evaded having to answer the charge of abandonment for three years by moving around and living for a time in France. Fake announcements of his death in Paris – purportedly in October 1843 – also appeared in London newspapers (presumably placed by William himself!), but, in 1845, he was brought to the Bristol Police Court where the prosecutor told the Magistrates that he would bring evidence to show that ‘the party before them was a disorderly person, a rogue and a vagabond’ for abandoning his family.

William’s response, through his lawyer, was that Frances had committed adultery and incest with her brother, James Kerr Jordan, which was the cause of William leaving her, and that an action for ‘Criminal Conversation’ was pending.

‘Criminal Conversation’ was an action for financial compensation which could be brought by a husband in the event of infidelity by his wife. To succeed in such an action, the actual act of infidelity had to be witnessed by a third party. Prince Henry, the Duke of Cumberland and Strathearn and brother of George lll, who was the first member of the Royal Family to become Grand Master of the Moderns Grand Lodge in 1782, once found himself on the wrong end of such an action which cost him £13,000 (worth about £1.5m today) for a youthful dalliance on a couch with politician’s wife, Lady Henrietta Grosvenor!

At the Bristol Police Court, it was further alleged by William’s lawyer that the charges had been brought at the instigation and expense of Frances’s brother in an attempt to use the court ‘as an instrument of injustice and oppression against a man who was complaining of his wife’. In addition to the action for ‘Criminal Conversation’, there were also divorce proceedings pending in which both parties were alleging adultery by the other and the magistrates should not ‘allow themselves to be made weapons in the hands of a third party to punish Mr Torckler, for it was evident that this was not a bona fide proceeding on the part of the parish’.

William deployed his charm once again when giving his evidence and, coupled with evidence to show that Jordan had indeed helped his sister and the parish to pursue the prosecution against William, this was enough to persuade the magistrates to dismiss the charge. They also dismissed a further charge that William ‘had rushed into Jordan’s house and seized some papers’ when William said that he’d only wanted to see his wife, who was in the house, and promised not to do it again

William’s action for ‘Criminal Conversation’ against his brother-in-law was another case which he withdrew at the last minute leaving costs unpaid. He alleged later that he was unable to proceed because his children had been taken to France by Jordan to prevent them giving evidence. Given that the oldest child would only have been about nine years old at the time of the alleged adultery and incest, it seems unlikely that any statements they were persuaded to make several years after the events would have been given much credence by a court.

However, in February 1846, the brothers-in-law were again in court in a case of libel brought against Torckler by Jordan in connection with ‘statements made in a circular’. The newspapers did not report what was said in the ‘circular’, but it’s probable that William had published the claim he’d made in court the previous year – that his wife had committed adultery and incest with Jordan, her brother. In this case, William again backed out at the last minute by admitting, through his solicitor, that ‘the imputations contained in the libel against the character of the Plaintiff (Jordan) were utterly destitute of any foundation in fact’. The Lord Chief Justice ordered that, after this complete disclaimer by the defendant, Jordan could do little better than take a ‘verdict by consent’ with 40 shillings damages and costs and the case was ended. Needless to say, William did not pay the 40 shillings or any of the legal costs, including those of his own lawyers.

In 1841, after his separation from Frances, William had mortgaged his £70 per year pension to the London, British and Foreign Insurance Company in return for a payment of £700. He spent some time in France and in several different parts of England, Wales and Scotland and had soon used up his capital. He rarely had any income from paid employment and incurred more large debts – some whilst using the name of Young rather than Torckler – and in his next appearance in a court in June 1846, just four months after backing down in Jordan’s libel action, he was declared bankrupt on his own petition and subsequently served seven months in the Queen’s Prison for debtors in Southwark, London.

His schedule of debts amounted to £2,477 (today’s value is around £235,000), of which £800 had been incurred in India 20 years earlier. His Indian debts were for outstanding loans of £600, a bill for wine of £150, and a clothing bill for £50. His English debts, incurred from over twenty-five different addresses in England and France, included his unpaid legal bills, accounts for board and lodging at twelve of his addresses, accounts for various goods from eleven different businesses, bills for schooling his children and several outstanding loans. It is surprising that he spent only seven months in the debtors’ prison as it was revealed in the “Great Masonic Trial” that none of his creditors ever received a payment.

William’s next engagement with the courts was in the following year in 1847 when Frances’s divorce case against him was finally concluded. Typically, he didn’t turn up at the first hearing in May. The divorce on the grounds of cruelty and adultery was granted, and William was held to be in contempt of court in his absence. In the following month, he appeared to appeal the contempt action and successfully proffered the excuse that he had been in prison for debt and was residing in Boulogne at the time of the earlier hearing. His charm again surfaced and his appeal was granted, but the divorce stood and was confirmed by the court. William and Frances were finally free of each other.

Note. Although William and Frances were now divorced, the case was in a church court and took place before the 1857 Divorce Act. It was, therefore, a ‘divorce from bed and board’ (a mensa et thoro, literally from table and hearth) which separated the parties but did not allow either to re-marry during the lifetime of the other. It could be granted on grounds of life-threatening cruelty, or of adultery by the husband or the wife.

A year or so went by, during which William kept up his acquaintance with the courts by suing a Mr Willey for breach of contract and then abandoning the case at the last minute, leaving the legal costs unpaid. He also did the same in a similar case against a Mr Watson. These gentlemen had allegedly agreed to engage his services as a tutor, but the work never materialised. In a later similar action against a Mr Landy, when William sued for the sum of seven guineas, the action was heard, but William failed to provide sufficient evidence to convince the court of the merit of his case. And in yet another action for breach of contract against a schoolmaster in Dublin, the case never reached trial as the Irishman tragically committed suicide by poisoning himself.

In 1849, William was advertising his services as a tutor at premises in St Georges Parade in Cheltenham and seems to have been deploying his charm with the ladies of the town. By the end of the year, when he was aged 45, he had set his sights on 15-year-old Susan White, whose father, William White, was in business as a shoemaker in Bath Terrace in Cheltenham. In the “Great Masonic Trial”, it was alleged that he abducted her from her parents – ‘this man, who had seen the roughs of life, who had seen enough to calm down the passions of nature, and knew that there was something that the World did not tolerate and which all shrunk from being a party to – what did he do? He went to Cheltenham and seduced a girl who was 15 years old. He took her away, although he had a wife and children living, and she lived with him as his mistress for 6 years…and then he married her’.

He was also accused of bigamously marrying Susan – or Susannah as she was then calling herself – because the 1847 divorce from Frances in a church court did not allow either party to re-marry during the lifetime of the other. He responded that he thought his first wife, Frances, had died before he re-married.

At the time of the 1851 census, William and Susan were living together in London at Cantler’s Place, St Pancras. Recorded as being married to each other, his age was given as 36 (he was actually 46) and her age was entered as 24 (she had just turned 17). The enumerator who collected the census information has added the note ‘the entries were obtained from the landlady of the house as W Y Torckler refused to fill up his schedule or to give any information whatever’. The enumerator must have been very annoyed and appears to have vented his wrath by faintly writing the word ‘FOOL’ next to William’s name on the census form where we can still see it today!

A Torckler child, named after his father, was born in Lambeth in 1854, but his death was recorded in the same month. Two years later, in 1856, William did indeed marry ‘Susannah’ in Wandsworth in London. Just to be sure, they married again (she was ‘Susan’ this time) in 1871 in St. Mathias, Earl’s Court, London. Perhaps he was just being romantic!

In 1859, William was once again in the Bankruptcy courts as a result of unpaid debts incurred from 11 different addresses in Middlesex, and he was committed to Whitecross Street Debtor’s Prison in London. Whilst there, he was involved in an altercation with other prisoners he accused of ‘behaving disrespectfully’ and complained to the authorities that his hat had been purposely damaged. He was detained in the prison for around eight months before his release, but never contributed anything towards payment of the debts.

In 1854, Frances had emigrated to Australia with her daughter, Harriotte, and she died in Queensland in 1875. In the public notice press announcement of the marriage of Harriotte in Australia, it was claimed that she was the granddaughter of the Hon. Jacob Jordan, Paymaster General of the British Forces and speaker to the Upper House of Assenmbly in Canada inferring that Torckler’s wife, Frances Eleanor Jordan, was the Hon. Jacob’s daughter. This was not so – Jacob died some 20 years before Frances was born and her father was actually a man named John Jordan, who might have been a descendant of the Hon Jacob.

Information as to how Frances got by during the few years between her divorce and her emigration is scarce, but in an item from August 1853 in the Morning Post, she is reported as having appeared at the Lambeth Court on a charge of ‘unlawfully obtaining possession of and detaining two children’ belonging to a Mr and Mrs Hakewell. In court, she described herself as ‘the widow of an officer in the army’ and refused to give her address. It seems she had unwittingly become involved in a marital dispute between the Hakewells and was caring for the children at Mrs Hakewell’s request, so the charge was withdrawn. The press report says that she was ‘recognised by Horsford, the mendicity officer, as a practised begging-letter writer’.

| PART THREE .….be especially careful to maintain in their fullest splendour those truly Masonic ornaments ……. Benevolence and Charity….. (The Ancient Charge) |

William himself was a prolific writer of begging letters, so Frances probably got the idea from him when she saw that they sometimes produced results. As you’d expect, William traded on his ‘fight for justice’ with the Government and the East India Company. In the “Great Masonic Trial”, he was alleged to have boasted to one of his landlords, a Mr Joseph Hughes, that the unfairness of his court-martial and being sentenced to hang, was the best thing that ever happened to him because it earned him a great deal of money over the years. An acquaintance reportedly also said that Torckler spent every morning writing his letters which he then sent out with his pamphlets and testimonials to support his requests for money.

He was not averse to issuing thinly veiled threats if his appeals fell on deaf ears and his charm failed him. He is occasionally mentioned in press reports of the committee meetings of churches as far north as Scotland which had received approaches from him. At one such meeting, the Rev Gerald Blunt, Rector of Chelsea, read out letters which he had received from William, parts of which said: ‘…..as the observations contained in a note at the foot of the enclosed paper have an injurious tendency affecting your public character, I do not deem it right to put it into circulation without your knowledge or without giving you an opportunity to deny or explain what is therein alleged. You may not deem the matter worthy of your notice; in that case, and in the event of my not hearing from you satisfactorily on the subject before Monday next, I shall consider myself at liberty to publish it…..’.

What had the good Rev Blunt done to deserve this? He had failed to give alms to ‘an idiotic boy’ who had approached when he was out walking with a colleague who gave the boy sixpence.

The ‘enclosed paper’ that William threatened to publish was a printed circular containing a long diatribe written in Torckler’s typical verbose style. The content of the ‘note at the foot’ was not reported, but probably identified the Rector. The opening paragraph of the circular gives an idea of its tone: ‘When an appeal such as this meets with little or no responsive echo in the breasts of the Ministers of the Gospel; the district visitors of the parish; or others whom it chiefly concerns; when Priests and Levites coldly and unfeelingly ‘look on it and pass by on the other side’ like those in the parable of the man who fell among thieves, each excusing himself by saying ‘it is no business of mine, it is out of my district’; when, with no better excuse, one Minister grudgingly contributes sixpence and the Rector of the Parish, nothing, out of the abundance with which God has blessed them……’ – there is great deal more of this kind of content and the circular then ends with- ‘…… a day of reckoning will surely and swiftly come.’

Unsurprisingly, the Rector also received a separate letter telling him that if he sent a ‘contribution’ to Torckler, he ‘need think no more’ on the subject and there would be no need to publish the circular to a wider audience.

The Rector explained to the meeting that he had some 50 such approaches for alms every day and, as he was outside his parish where he had 20,000 other poor persons to attend to, he was unable to give money to persons in other districts. Those present advised him to ignore it, telling him that Torckler had ‘been before the Guardians’ on a previous occasion and a Dr Scatliff was known to have had similar difficulties with him. Maybe Torckler had slipped ‘the idiotic boy’ a penny and told him to approach the Rector!

William had also boasted to his landlord, Joseph Hughes, about another ‘poor clergyman in St John’s Wood’ who had ‘a secret’ of which William had become aware and from whom he had extracted ‘a great deal of money’. It must have been a tremendous shock for William when he arrived at the Court for ‘The Great Masonic Trial of Torckler v. Tattersall’, to discover that his landlord, Joseph Hughes, to whom he had unashamedly boasted about some of his lucrative misdeeds, was working as an investigator for Mr Bretherton, the barrister acting in the Rev Tattersall’s defence!

When questioned about the clergyman of St. John’s Wood during ‘The Great Masonic Trial’, Torckler said ‘he was not so much to be pitied, for he was a poor wretch’. But being a ‘poor wretch’ was no protection from William’s machinations – if there was cash to be had, William would take it no matter how poor his victim was. The trial also revealed that he had written letters containing threats to a person with whom he had lodged in Tranmere and had insulted a Rev. Spungeon when the Rev. had refused to give him money.

According to his own testimony, William became a Freemason in 1853 and it was around this time that, in addition to his other victims, he started targeting Lodges and individual Freemasons in places such as Leamington, Cheltenham, Manchester, Dublin and London with approaches for contributions to his coffers. In the manner of many sharp operators, to succeed with his manipulations he must initially have radiated a certain charm – the same kind of charm, perhaps, that enabled him to coax a teenage girl who was 30 years his junior to become his mistress. But if his designs were thwarted, he was equally adept at intimidation.

| PART FOUR …..let Prudence direct you. Temperance chasten you and Justice be the guide of all your actions….. (The Ancient Charge) |

So what had the Rev. Tattersall, Vicar of Oxton and Chaplain of the Mersey Masonic Lodge in Birkenhead, done to incur Torkler’s wrath and give rise to ‘The Great Masonic Trial’?

It all started when the Vicar was approached at his home for a donation by Torckler, who had been petititioning for cash from Lodges and members in Liverpool and was now trying his luck in Birkenhead. He said that other members of the Mersey Lodge including a Bro Ward and a Bro Craig, had given him a sovereign each and a Reverend Knox had given him ten shillings. He called again the following day when the Vicar told him that he would also give a sovereign, but he would first need to make enquiries to ensure Torckler was a worthy recipient. On Torckler’s third visit, the Vicar had not yet made his enquiries, but told his wife to give Torckler ten shillings.

On the following day, the Vicar found out that the brethren named had not given donations to Torckler and also received an ‘impertinent note‘ from Torckler complaining that he’d been given only ten shillings after being promised a guinea and quoting a biblical sounding phrase (which isn’t from the bible!): ‘Promise to thy neighbour and deceive him not, even though it be to thine own hurt’.

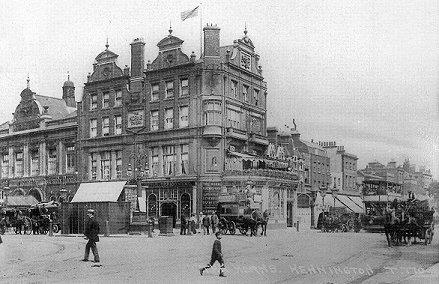

A couple of days later, Torckler and the Reverend Tattersall encountered each other walking on opposite sides of the street in Toxton. Torckler gestured and raised his hat and Tattersall called out along the lines of “I have received that impertinent note of yours. Do not come to my house again. You are a vagabond and an imposter”. Torckler then crossed the street and angrily responded with “you are a liar. Lies, lies, lies“. Things degenerated from there when the Vicar accused Torckler of obtaining money under false pretences and the bad-tempered confrontation then moved off the street into the nearby Queens Arms Hotel.

Inside the hotel, Torckler completely lost his temper. He allegedly called the barmaid, Mrs Andrews, a ‘strumpet’ and a ‘vixen’ and accused her of being the Vicar’s ‘fancy woman’. Much shouting and fist-waving went on and Mrs Andrews grabbed hold of Torckler’s beard. Then a policeman turned up – Torckler was restrained and a window was broken in the struggle. When the Vicar repeated his accusations that Torckler was a vagabond and imposter and had obtained ten shillings from him under false pretences, William was taken into custody and locked-up overnight.

The following day, a Friday, he was brought before a magistrate where he said he would apologise to the Vicar if he agreed not to press charges. However, Police Superintendent Hammond asked that Torckler be remanded as he had papers on him that indicated he could be a regular begging imposter. The magistrate agreed and Torckler was returned to the cells until the Monday morning when, enquiries having been completed, no charges were laid and he was released from custody.

When Torckler was released, he agreed to leave the area. So it must have come as a tremendous shock to the Rev Tattersall when Torckler once again resorted to the courts seeking £5,000 compensation (today’s value is almost half a million pounds) for ‘giving him into custody on a false charge of misdemeanour; maliciously giving him into custody on a false charge of obtaining money under false pretences ….. and falsely and maliciously saying to him “you are a vagabond and imposter and have obtained ten shillings from me by false pretences” ‘.

The case came up at Liverpool Winter Assizes in 1868 before Mr Justice Lush who suggested that it be referred for arbitration to Mr C J Preston, the stipendiary magistrate of Birkenhead. The suggestion was accepted and the proceedings were conducted by Mr Temple, barrister, for Torckler and Mr Bretherton, solicitor, for the Rev Tattersall.

The hearing, in March 1869, lasted six days and largely consisted of the investigation into the life and activities of William Young Torckler as summarised in the earlier parts of this tale.

Mr Bretherton, on behalf of the Reverend Mr Tattersall, in a very long address, pointed out that ‘this man, who had been in prison, who had deserted his wife and children, who had been guilty of bigamy, who had received hush money, estimated his character’s worth at £5,000. If the arbitrator could entertain that any one of the counts entitled Torckler to a verdict, then it must be the lowest coin of the realm’. ‘When a man came before them claiming £5,000 damages for his character, that character should be as pure as they conceive the character of erring man to be. It must be shown that the character was not of such a nature that the man would be better to have paid treble the money to get rid of his character than to stand up there and say it was damaged’.

Mr Preston, the arbitrator, was persuaded and he ended the proceedings after due deliberation by awarding Torckler damages of twenty shillings, with each of the parties to pay their own costs.

Torckler, true to form, paid nothing and filed for bankruptcy again, whilst the Rev Tattersall took a leaf from Torckler’s book and appealed to local freemasons and churches for help in meeting his liabilities which amounted to £500 (around £46,500 today).

The Liverpool Daily Post of Saturday, 26 February1870, reported “the costs incurred by the Rev Tattersall were so heavy that it was necessary for a subscription to be raised among some friends to defray them. The funds raised fell short of the requirements, and the Rev gentleman called his creditors together with a view to an arrangement. A deed was prepared and assented by most of the creditors, accepting four shillings in the pound at once, and five shillings more in instalments spread over two years, but all did not agree. One of them, Mr Joseph Hughes of London , who had been employed to find out the antecedents of Torckler, succeeded in upsetting the arrangement and obtaining a writ against the Rev gentleman. This was put into execution and Hughes was, up to yesterday, in possession of the vicar’s house and furniture. In the meantime, Messrs. Bretherton, acting for the Rev Tattesall, have obtained an injunction to restrain Hughes from selling the property.”

Subsequently, two months later, a legal action seeking possession of the house from Hughes was commenced by a Mr Tilby acting as ‘representative of friends of Mrs Tattersall’ and a bill of sale was produced proving that the house was not owned by the Rev Tattersall at the date possession was granted to Hughes. The case was heard before a jury who found in favour of Mr Tilby and the Tattersalls were able to move back into their home.

William Young Torckler, having had his strange career and means of income revealed, kept a relatively low profile afterwards and died aged 81 in 1885 in the city of Bath. His second (possibly bigamous) wife, Susan, sailed to New Zealand in 1903 with her daughter, Laura, and died in Wellington in 1911.

The Reverend William Alfred Tattersall, MA, continued his duties as the Vicar of Oxton until his death aged 55 in Birkenhead in 1884.

The ‘Great Masonic Trial’, so named because it involved Freemasons on both sides and created much comment amongst Masonic fraternities, started with ‘a storm in a teacup’, yet cost the 19th Century equivalent of many thousands of pounds, nearly ruined a ‘Man of God’ and benefitted no-one.

There must be a lesson here for all of us.

.

inside the building barricaded themselves into offices. Around a thousand people gathered in the street waiting to see either the ‘capture or the kill’ and State Troopers were called to clear a space in front of the building and keep order. It was two hours later when a team from the Zoo arrived with a cage into which Wallace proudly strutted after his adventurous day out.

inside the building barricaded themselves into offices. Around a thousand people gathered in the street waiting to see either the ‘capture or the kill’ and State Troopers were called to clear a space in front of the building and keep order. It was two hours later when a team from the Zoo arrived with a cage into which Wallace proudly strutted after his adventurous day out.

e was a joining member of ‘Duchy of Cornwall Lodge No 3038’ which then met at the Café Monico in Shaftesbury Avenue. He served as Worshipful Master in all three Lodges, being the youngest ever WM of Rye Lodge in 1913, and remained a member of all three Lodges throughout WW1 and the following years, earning his first London Rank in 1927. In around 1920, he was also a founder member of ‘Outre Manche – Across the Channel Lodge No 14’ in Calais.

e was a joining member of ‘Duchy of Cornwall Lodge No 3038’ which then met at the Café Monico in Shaftesbury Avenue. He served as Worshipful Master in all three Lodges, being the youngest ever WM of Rye Lodge in 1913, and remained a member of all three Lodges throughout WW1 and the following years, earning his first London Rank in 1927. In around 1920, he was also a founder member of ‘Outre Manche – Across the Channel Lodge No 14’ in Calais.